AUTO-RETRATO SOBRE PAISAJE PORTEÑO

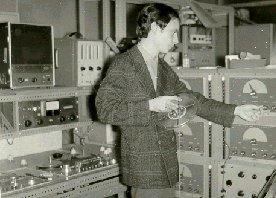

Jorge Antunes, em 1969, no Laboratório de Música Eletrônica do Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, em Buenos Aires.

Auto-Retrato Sobre Paisaje Porteno (14m 22s)

A obra Auto-Retrato Sobre Paisaje Porteño, do compositor brasileiro Jorge Antunes, foi composta em 1969, no Laboratório de Música Eletrônica do CLAEM, Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales do Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, em Buenos Aires. A peça, que tem duração de 14'50”, representa a busca por uma definição estética e de um domínio do material sonoro.

Antunes serviu-se de um disco de gramofone – uma chapa – em que estava gravado um tango com Francisco Canaro, comprado no subúrbio de Buenos Aires, em um brechó de Caminito, em La Boca. Na loja de objetos usados, Antunes comprou também um velho gramofone. No Laboratório do CLAEM, ao tocar o velho disco, Antunes percebeu que o braço do gramofone era pesado: a agulha quase penetrava no acetato do disco. Um defeito, assim, fazia com que uma trilha se repetisse continuamente. Esse defeito tornou-se efeito especial, fornecendo o elemento rítmico básico para a construção de um samba que, misturado a uma célula do tango, deu lugar à integração do compositor na paisagem portenha.

A inovação corajosa em usar sons de um disco velho e o próprio ruído do disco criou polêmica no meio musical, pois a música eletroacústica institucionalizada, na época, era radicalmente contra o chiado, chamado suplido em espanhol e souffle em francês. A “limpeza” sonora, sem ruídos, era um tabu. Nas décadas seguintes a ideia original de Antunes foi copiada por outros compositores, que encontraram fonte de inspiração em discos antigos e ruidosos.

A vontade de construir uma paisagem, sobre a qual Jorge Antunes pretendia pintar um auto-retrato, era motivada pela semelhança política vivida pelos dois países: Brasil e Argentina. O compositor ganhara a bolsa de estudos do Instituto Torcuato Di Tella que lhe proporcionava o exílio no momento justo: o regime militar brasileiro, após a promulgação do AI-5, lhe perseguia. A Argentina, país que o acolhia, por ironia também começava a viver momentos de dura ditadura militar, sob o governo do General Ongania.

Na última seção da composição musical a voz de Antunes é utilizada para a inflexão de um discurso cujas palavras nada significam. As palavras-chaves percebidas traduzem a preocupação do compositor diante da situação política latino-americana em fins dos anos 60. O discurso termina com uma improvisação vocal, em que Antunes brinca com as palavras “geral” e “general”, em alusão aos donos do poder na época.

Essa música de forte conotação política criou polêmica e problemas. Em 2009, em visita a Buenos Aires, Jorge Antunes teve acesso ao acervo histórico do Instituto Torcuato Di Tella e da coleção Mary Reichenbach. Verificou então que a obra sumiu do acervo, tendo sido, em 1972, banida dos arquivos do CLAEM. As outras obras de Antunes realizadas na época estão lá arquivadas. Mas o polêmico Auto-retrato desapareceu.

O final da obra forma estereofonicamente, com efeitos vocais, algo como a assinatura do autor: JO-EU.

The work Auto-Retrato Sobre Paisaje Porteño, by the Brazilian composer Jorge Antunes, was composed in 1969 at the Electronic Music Laboratory of the CLAEM, Latin American Center of Superior Musical Studies of the Torcuato Di Tella Institute, in Buenos Aires. The piece, which has a duration of 14 minutes and 50 seconds, represents the search for an aesthetic definition and a domination of the sound material.

Antunes used an old-fashioned gramophone recording – a plate - with a tango by Francisco Canaro, purchased by the author in a junk shop in Caminito, in the La Boca district of Buenos Aires. In the second-hand store Antunes also bought an old gramophone. In the CLAEM laboratory, when he played the antique recording, Antunes perceived that the arm of the gramophone was heavy: the stylus nearly penetrated the acetate surface of the plate. A scratch would cause the sound track to repeat itself continuously. This defect became a special effect, providing the basic rhythmic element for the construction of a samba, which, when combined with the cell of the tango, opened the way for the composer’s integration with the Buenos Aires landscape.

This audacious innovation in using sounds from an old recording, together with the noise of the disk itself, sparked controversy in the musical world, since instutionalized electroacoustic music at the time was radically opposed to squeaks, called “suplido” in Spanish and “souffle” in French. Cleanness of the sound, without noise, was the rule. In subsequent decades Antunes’s original idea was imitated by other composers, who discovered sources of inspiration in noisy old recordings.

The desire to assemble a landscape, over which Antunes intended to paint a self-portrait, was motivated by the political similarity experienced by the two countries: Brazil and Argentina. The composer had won the fellowship from the Torcuato Di Tella Institute, which offered him exile at just the right moment: the Brazilian military regime, after the promulgation of the AI-5, was hounding him. Ironically, Argentina, the country that welcomed him, was also beginning to undergo a period of tough military dictatorship, under General Ongania’s government.

In the final section of the musical work, Antunes’s voice is used to inflect a speech whose words have no meaning. The key-words which are recognizable translate the composer’s concern with the political situation of Latin America in the late 60's. The speech ends with a vocal improvisation in which Antunes plays with the words “geral” (general) and “general” (army officer), referring to the powermongers at that time. This work with a strong political connotation generated controversy and problems. In 2009, during a visit to Buenos Aires, Antunes had access to the historical archive of the Torcuato Di Tella Institute and the Mary Reichenbach collection. He discovered that the work had disappeared from the archive, having been banned from the CLAEM archives in 1972. Antunes’s other pieces written at the time are there in the archives. But the controversial Auto-retrato had vanished. The end of the work forms, stereophonically, with vocal effects, something resembling a sound-signature of the author: JO-EU (Me-Me).